The New Oxford Book of War Poetry Edited by Jon Stallworthy | Books in Review

The New Oxford Book of War Poetry (Oxford University Press, 448 pp., $29.95) starts with the Bible and works its way to modern times. The youngest poet I spotted in this book was David Harsent, who was born in 1942, the same year I was born. He is in the age group referred to in English literature classes as “young poets.” I hope he feels younger than I do.

The New Oxford Book of War Poetry (Oxford University Press, 448 pp., $29.95) starts with the Bible and works its way to modern times. The youngest poet I spotted in this book was David Harsent, who was born in 1942, the same year I was born. He is in the age group referred to in English literature classes as “young poets.” I hope he feels younger than I do.

The book, edited by Jon Stallworthy, contains fewer than a dozen poems by Vietnam War veterans. The arrangement of the poems in this large book—with no subject categories—makes it difficult to determine exactly how many deal with particular wars. The book is arranged roughly in chronological order, but the lack of subject arrangement is a serious lapse and does not make this an easy reference book to use. Nor does the fact that it’s printed on cheap paper.

Patrons come into a library looking for poems that deal with a specific war or wars. To find them in this book, you need to know the name of the poet associated with a particular war. Yes, birth dates help, but not a lot.

I used the birth dates of the poets as a rough guide to locate poems dealing with specific wars. Doing that, I generally found that the book included most-often-cited poets for each war. For the Vietnam War, for example, there was the work of Yusef Komunyakaa, W. D. Ehrhart, Bruce Weigl, John Balaban, along with one unusual suspect, Ngo Vinh Long. This group gets a total of seven poems between them.

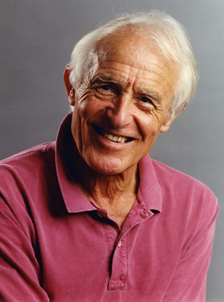

I read the introduction to find out why the volume contains so few poems by Vietnam veterans. Editor Jon Stallworthy—a poet and Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Oxford University and a Fellow of the British Academy—explains it clearly: “For demographic and socio-historical reasons, ” he writes, “the ratio of poets to other servicemen and women was less than in either world war. Most American intellectuals disapproved of the Vietnam War, and men of military age, particularly white men of military age, could avoid conscription by signing up for university education, and many did.”

Jon Stallworthy

As a university-educated white man and an intellectual who disapproved of the Vietnam War, where do I begin to take issue with this explanation? Is Stallworthy saying that those of us who served in Vietnam were too dumb or uneducated to write poetry? I think he is—albeit hidden inside a velvet glove.

Since I wrote poetry while I was in Vietnam—just as many World War I poets wrote poetry during their war—I accuse Stallworthy of either not doing enough research or not reading enough Vietnam War poetry. Tens of thousands of university-educated men and women served in Vietnam. What’s more, many other men and women who took part in the war and who did and did not have university educations wrote worthy poetry after coming home from Vietnam.

I found nine poems by Wilfred Owen in the anthology. Many Vietnam veteran poets wrote nine or more worthy poems. You will not find them in this book.

The American poet of the Vietnam War who Stallworthy singles out for the most attention is John Balaban. He served in Vietnam as a conscientious objector, and is a fine poet, a very brave man, and an old friend. One of the best memories of my life is the day he showed up to read poetry to my Vietnam War class. But why not a few words about Bill Ehrhart? Space constraints, no doubt. Ehrhart was a Marine in Vietnam.

Don’t look in this anthology for much in the way of poetry dealing with wars since Vietnam. There is one fine poem by Peter Wyton, who was born in 1944, “Unmentioned in Dispatches, ” that deals with the Iraq War.

—David Willson