The Moral Life of Soldiers by Jerome Gold | Books in Review

Jerome Gold, who served in the U. S. Army Special Forces during the Vietnam War, divides his book, The Moral Life of Soldiers (Black Heron Press, 270 pp., $16.95, paper), into two sections. Part One is comprised of five short stories of varying lengths. One of them (“Paul and Sara, Their Childhood”) is long enough to be called a novella. Part Two consists of one story, “The Moral Life of Soldiers: The American Education of a People’s Army Officer.” It is a short novel of 132 pages.

Fans of Gold’s work will have encountered four of these stories, and parts of the fifth, “Paul’s Father.” Most of “The Moral Life of Soldiers” is new to this book.

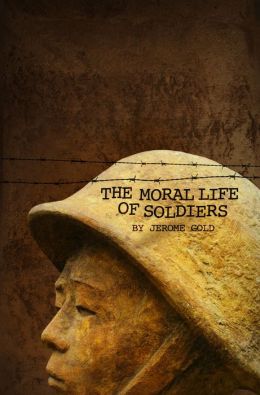

The cover art and design by Bryan Sears is one of the most striking Vietnam War book covers I have seen. It features a depiction of most of the face and head of a People’s Army Officer in a helmet with a chin strap. It seems sculpted from clay. Physically, this is a beautiful book.

It is a beautifully written book, too. It contains a lot of good stories—stories so good that they all held my attention, even though I had read some of them before, years ago. Every one of the stories in the book deals with the relations between men and between men and women. The stories show us that the price of love can be steep. I’d forgotten how often war intrudes into the lives of the characters in these stories. It was good to be reminded.

The difficult relations between races and different ethnic groups is also explored in these stories: black and white, white and Asian, white and Hispanic. None of the relationships in the book are easy.

Gold gives the great short story writer Raymond Carver a run for his money in these stories, especially in “John” and “Concealments.” If Carver read the story, “John, ” I’ll bet he’d wish he’d thought of setting a story in a gas station restroom. I know I did. The setting becomes a character in the story. It is a tour de force.

The theme that unites the stories in this book most powerfully is culture conflict—cultures in collision. People from the North of the United States move to the South where Jim Crow is still in fullest flower and little kids encounter separate drinking fountains for blacks and whites. Violence ensues.

The five stories of the first section also have characters in common, characters we become involved with, wonder about, even worry about. That’s where Gold’s art as a storyteller pulls us into his realm.

The second half of the book is dominated by a character out of his culture. He’s a Vietnamese man surrounded by American Special Forces soldiers. They view him as a little guy, the other, not like them. And he is not like them. But he is also like them. It’s complicated.

I chose to read the second part of this book first. The subtitle—“The American Education of a People’s Army Officer”—goes a long way toward encapsulating the story of this 132-page novella. Racism and culture conflict are at the center of it. They are also at the center of the American war in Vietnam. The Vietnamese lieutenant who is the first-person narrator and main character is underestimated and misunderstood throughout this tale, very much as we, the Americans in South Vietnam, underestimated and misunderstood our allies and the enemy.

The Vietnamese lieutenant completes Special Forces training as part of an officer exchange program between the United States and South Vietnam. Then he serves with a Special Forces Group in Central America. “I was a special staff officer of the group for more than a year, ” he says.

Jerome Gold

The first-person narrative of the story involves the reader. The intimacy of the narration makes the reader forget that this is fiction, so convincingly does the author succeed in inhabiting the consciousness of the Vietnamese lieutenant. Occasionally, I was reminded of the stories of Robert Olen Butler in A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain , which also is written by an American author from inside the heads of Vietnamese characters.

But Gold is his own man, and this story is very different from Butler’s. The lieutenant (now a retired colonel covered in glory) states early on that his “purpose in composing this memoir is not, or at least not only, to explore the moral life of soldiers.”

And this novella is much more than that. We are shown in one powerful scene after another how awkward and inadequate and ill-prepared American soldiers are to deal with people in cultures other than their own. Our narrator also explores the sorrow to be found in relationships with women.

The lieutenant is not the only character who is very well delineated in this novella. Sergeant Donaldson is the lieutenant’s closest American friend, which cuts across cultural lines and also against Army rules about officers fraternizing with non-commissioned officers. The Vietnamese lieutenant encounters suspicion and cultural barriers too great for him to find acceptance with the American officers, so he associates with the sergeants in their club, particularly Donaldson.

This is an engrossing story and also a tragic tale—of soldiers and of a tragic unnecessary war that killed millions.

No character in this novella—not even the well-drawn female ones—is more tragic than Sergeant Donaldson, who sums up the fate of the soldier as “romantic fatalism, ” when he says, “I am a soldier. I go where they tell me to. “

I felt a huge connection with him when he said that. I’ve used similar words myself many times when I’ve been confronted by veterans of the American war in Vietnam who served in the infantry.

“Why did you stay safe in the rear with the beer and the gear? I would have grabbed an M-16, hitched a ride out into the boonies and got me some. It’s guys like you who lost that war for us. If you’d had any balls, you could have at least volunteered to be a helicopter door gunner.” And so on.

My answer: The Army told me what they wanted me to do and trained me to do it. Sergeant Donaldson said it well. Sometimes a soldier would rather not do what he is ordered to do. Gold’s character speaks for me better than I could for myself.

Jerome Gold’s powerful aphoristic writing made this book a great pleasure to read. My favorite nugget of wisdom was from the retired colonel. To wit: “Perhaps patriotism begins with the love for a single person.” The word “perhaps” is the crucial one. Another of my favorite lines: “…the paths our lives take are not made by us, but exist to be discovered.”

Betrayal of friendship, war as a justification for killing, and what compels a man to select women to love–women who will always betray him—are the themes at the heart of this novella.

We learn what caused the American-trained Vietnamese lieutenant to join the National Liberation Front and rise to the rank of colonel. He used his training and experience with the Americans against us. But then he left the military and became a poet. That choice made me chuckle.

On the first page of his story, he makes it clear that his mother disapproved of his pursuing the literary life of being a poet. That scene linked me emotionally to him from the get-go, as I’d had that very same conversation with my own mother.

The dialogue went something like this:

“Can poets make a living doing that? Writing poetry?”

“Not usually.”

“Well, then, why do it?”

The retired colonel tries to return to poetry “after half a lifetime away from it.” Good luck with that. There’s a whole generation of old soldiers turning to the literary life now if my huge stack of new books written by Vietnam veterans is any indication. Most try hard and fail miserably.

Jerome God is a Vietnam veteran who is a great storyteller and a brilliant writer. But don’t take my word for it. Read this book and find out for yourself.

—David Willson