Selma to Saigon by Daniel S. Lucks | Books in Review

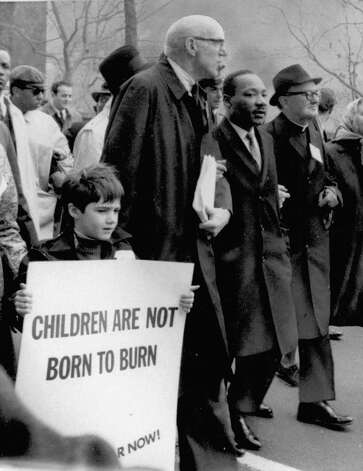

On August 12, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr., startled the Johnson Administration—and the nation—when he spoke out for the first time in favor of ending the American war in Vietnam. “Few events in my lifetime have stirred my conscience and pained my heart as much as the present conflict raging in Vietnam, ” King said in an address at the annual convention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. “The day-to-day reports of villages destroyed and people left homeless raise burdensome questions within my conscience.”

On August 12, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr., startled the Johnson Administration—and the nation—when he spoke out for the first time in favor of ending the American war in Vietnam. “Few events in my lifetime have stirred my conscience and pained my heart as much as the present conflict raging in Vietnam, ” King said in an address at the annual convention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. “The day-to-day reports of villages destroyed and people left homeless raise burdensome questions within my conscience.”

As Daniel S. Lucks points out in Selma to Saigon: The Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War (University Press of Kentucky, 394 pp., $35), even though King did not castigate the Johnson Administration (he called on all sides to “bring their grievances to the conference table”), the President and his allies were furious that the civil rights leader deigned to speak out against the war.

“Criticisms of America’s policy in Vietnam by civil rights groups, ” George Weaver, Johnson’s African-American Assistant Secretary of Labor, said in a speech, “could lead the communists to make disastrous miscalculations in American determination.”

Then, in January of 1966, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) came out against the war—the first time a Civil Rights organization formally went on record opposing American policy in Vietnam. SNCC’s main argument was that African Americans had no business fighting for freedom in South Vietnam when they were still struggling for many of those same rights in the United States, especially in the South.

That’s one aspect of the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement that historian Luck analyzes in this deeply researched book. He also looks at the often bitter disagreements within the movement that the war caused, and the repercussions those disagreements produced.

“For African Americans, ” Luck writes, “the emotional debates over the war aggravated fissures within the civil rights movement along generational and ideological lines.” By 1966, he says, “the war had siphoned the moral fervor from the civil rights struggle, exacerbated schisms within the civil rights coalition, and cost the lives of thousands of young African American men.”

For African Americans, he concludes, the Vietnam War “had a tragic subtext. It divided African Americans and the civil rights movement more than any other issue in the twentieth century. It left painful scars, which burned with a unique intensity. Decades later, many of these scars have not healed.”

—Marc Leepson